Martello Court

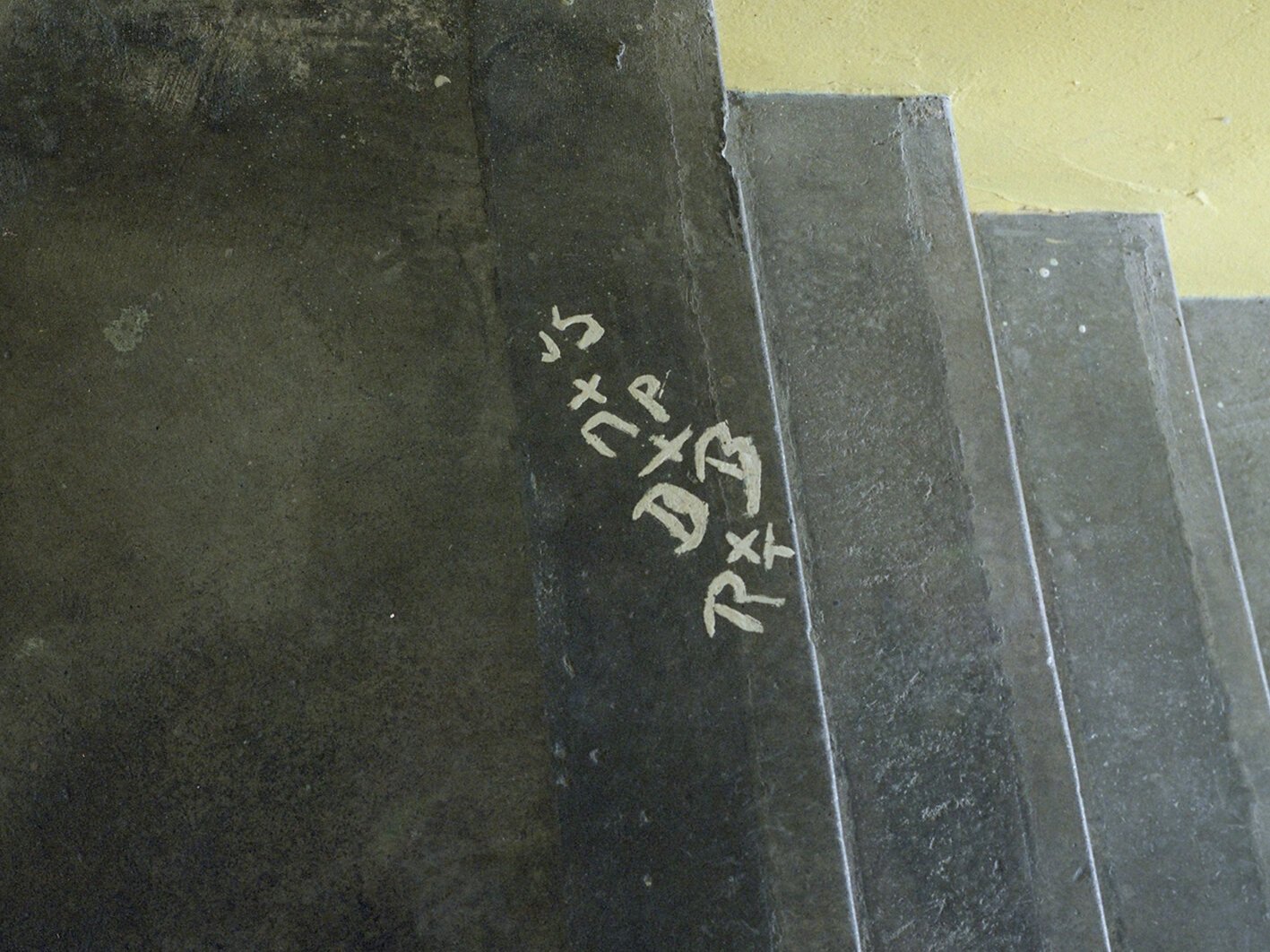

There is a lot of discussion at present about what our towns and cities will look and feel like in the post-COVID world. A death spiral of economic activity and loss of both permanent and transient populations, could lastingly render the centres barren wastelands, redundant in many different senses. With tourist numbers in decline and employees choosing to work from home, the whole service infrastructure required is becoming obsolete. The flip side, is that people are fostering an interest in localism, in how peoples’ immediate environment can serve their daily and weekly needs by starting to re-imagine what life could be like without the imperative for travelling and commuting for entertainment, employment and enjoyment. In a sense, much of this reconfiguration has already taken place. Many of the communities housed in the areas surrounding our big cities have changed dramatically in the last three decades. They are urecognisable from what they looked like, at least, in the past. Whilst many of these changes have been cosmetic, masking deep, underlying societal problems, there’s no doubt that by altering their physical appearance, many of our peripheral housing estates, for example, have been given an outward appearance of change and improvement. One such place is Muirhouse, one of a collection of housing schemes in the north of Edinburgh developed in the 1950s as the original process of reconfiguring the city’s centre took place. This involved slum clearing – some would say slum cleansing – scattering the capital’s population to the edges of the city, dispersing communities and displacing many of the chronic problems largely out-of-sight on Edinburgh’s fringes. To anyone growing up in that era, places such as Muirhouse were often labelled with descriptions such as ‘notorious’, ‘violent’ or ‘deprived’ and were seen, if they were ever looked at, as a blight on the city, best ignored and forgotten about. The architecture was grey and brutal, with the area being dominated by the Soviet-style Martello Court, a 200-foot, 23 story edifice which became the epicentre and synonym for all the area’s problems. Almost 30 years ago, network photographer John Sturrock chronicled the community as part of the Positive Lives - Responses to HIV photodocumentary project which graphically laid bare many of the challenges facing the people of Muirhouse at the time: crime, poverty, drugs, disease. Nevertheless, what was also communicated was a strong sense of resistence and community camaraderie. A feeling that people could, and would, survive. In recent years, Document Scotland has featured the work of two other photographers who have both made work on the estate: Yoshi Kametani’s often wry and colourful portrait of the place and Paul Duke’s No Ruined Stone, an insider’s view, which laced reality with positivity. This year, as the privations of lockdown gripped the nation, photographer Paul S. Smith embarked on his own project to document and interpret life in Muirhouse. Born in England, Paul’s family moved to Edinburgh when he was a boy, and he grew up in one of the more leafy areas of the city outside of Muirhouse. His memories tally with those of so many of the place, negative stereotypes reinforced by hearsay, rumour and suspicion. It is to his credit that, three decades on, he has chosen to revisit his childhood and confront these memories and prejudices. Colin McPherson, ‘Returning to Muirhouse: Martello Court’, 11th September 2020